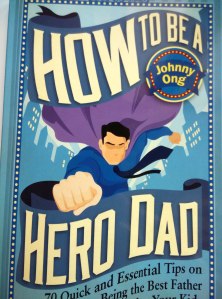

How to be a Hero Dad by Johnny Ong is a succinct, easy to read and clearly organized parenting guide for Dads who simply want to know what to do. Ong, a trainer for both children and parents, has been heartened by the increasing numbers of fathers attending his workshops, talks and seminars in their quests to be Hero Dads. Ong’s 20 years of fatherhood coupled with his interactions with thousands of parents and children put him in a unique position to empower his readers to achieve their parenting goals.

How to be a Hero Dad by Johnny Ong is a succinct, easy to read and clearly organized parenting guide for Dads who simply want to know what to do. Ong, a trainer for both children and parents, has been heartened by the increasing numbers of fathers attending his workshops, talks and seminars in their quests to be Hero Dads. Ong’s 20 years of fatherhood coupled with his interactions with thousands of parents and children put him in a unique position to empower his readers to achieve their parenting goals.

Ong’s vision of a Hero Dad is accessible to the everyday father: he defines a Hero Dad as “not about being great in extraordinary things [but] about making extraordinary efforts to be a great father” (xii). The book’s first five chapters are dedicated to what a hero dad does, namely, Love, Motivate, Discipline, Develop His Child’s Potential and Care about Education. Each of the chapters is then broken down into subsections, which begin with inspiring quotes and outline exactly how Dads can fulfil each of the qualities of a Hero Dad.

The first chapter Love is one of the book’s standouts, highlighting one of the most critical but often neglected aspects of parenting: knowing and discovering a child’s love language, which is the means by which a child is best able to receive love.

To help his readers see things from the child’s perspective, Ong also describes how many children in his workshops feel insecure about whether their parents really love them. He declares that this “ambiguity has to be removed from the children’s mind with the use of love languages [because] a child who feels unloved will not realise [his or] her full potential” (4).

In Motivate, Ong urges parents to identify their parenting style, which is either an authoritarian, authoritative or permissive one, or a blend of the three. Ong explains how each style has different implications for the child’s psychosocial development, affecting various domains ranging from their self-esteem, social competence and academic achievements to happiness.

The follow-up chapter Discipline is an excellent complement to Motivate, and will provide deeper insights after parents have identified their parenting style. Ong asserts that discipline must be distinguished from punishment. He defines the former as a “combination of parental example, instruction, and correction that teaches a child to live according to family values and rules, in harmony with society and culture” (61). In contrast, he links punishment with vengeance and retribution for an offence, which do little to teach the child how to behave.

Develop His Child’s Potential, another noteworthy chapter, delves into the concept of Multiple Intelligence developed by Harvard University professor Howard Gardner. The eight different forms are musical, visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily kinaesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and naturalistic. Ong expresses that Gardner’s theory was a revelation of sorts for him, given that he used to have a very narrow definition of intelligence centred on test scores and grades.

Ong’s sentiments about intelligence will no doubt be shared by many Singaporean parents who have been influenced by our society’s emphasis on paper qualifications. Ong encourages parents to adopt a more holistic approach and nurture their children’s intelligence beyond academic pursuits. Doing so will not only boost children’s self-worth but enable them to thrive in an evolving globalized world that demands more creativity and resourcefulness.

In Care about Education, Ong cites studies demonstrating that kids with involved, caring dads are more likely to perform well, enjoy class, participate in co-curricular activities and graduate from school. At the same time, Ong is careful to stress that dads do not obsess over grades and should instead allow their kids to revel in the learning process.

In the chapter’s sub-section “Play Is as Important as Studying”, Ong explains that education should enable a child to exercise creativity and capacity for innovation. Play is a large part of education because it renders numerous benefits such as honing a child’s social skills, cognition and imagination. Ong reminds parents that “it is through play that children learn things that no book or class or teach” (139).

In the second to last chapter Ten Things a Hero Dad Is, Ong lists various traits such as resilience, compassion, humility and optimism that Hero Dads embody. For each trait, he elaborates on how they play out in daily life and impact healthy child development, while exemplifying his points with his personal experiences.

Having sketched out the essential traits of a Hero Dad, Ong then cautions Dads against succumbing to the Ten Things a Hero Dad Is Not. On his list are “I Must Never Make My Children Feel Rejected” and “My Children Must Never Think I Am Made of Stone”. The latter is particularly salient in an Asian context prizing stoicism, which has resulted in many dads feeling afraid of expressing emotion.

Ong conveys to dads that emotions are nothing to be feared and are a powerful psychological force, playing a major role in a child’s life. Dads must remember that it means everything to their children to be able to get a glimpse into their emotional landscape.

How to Be a Hero Dad is a must read for time-pressed Singaporean Dads who want access to nuggets of wisdom without having to decipher fancy words and long arguments. All they need to do is flip open a page of the book and practise a tip a day, to move towards becoming the Hero Dad their children need and want.

How to be a Hero Dad is available in Singapore’s Public Libraries.

Copies can be purchased from the following bookstores: Popular Bookstores, Kinokuniya, MPH and Times Bookstores as well as at Armour Publishing Online.

About the Author : The Dads for Life Resource Team comprises local content writers and experts, including psychologists, counsellors, educators and social service professionals, dedicated to developing useful resources for dads.